Lady Gaga playing football. Is this really the best I could come up with when thinking about what ‘popular culture’ is?

During an introductory lecture on my 2nd year ‘Popular Culture in Early Modern England’ course, I recently outed myself as hopelessly out of touch with the times. Struggling to think about what ‘popular culture’ is in today’s world, I tried to think of examples which today’s generation of future leaders could relate to. I should have put some thought into this in advance of the session! It went something like, “err Lady Gaga and football, and I’m hopelessly out-of-date here I realise, but Breaking Bad perhaps”. I looked a bit foolish. The funny thing is, though, that I think this only served to reinforce the overall point of the lecture as a whole. ‘Popular culture’, such as it can be defined at all, is not a homogenised and uniform experience – its not some monolithic entity with clear boundaries and neat subdivisions. It cannot be easily nailed down or categorised, let alone analysed. My popular culture involves trying to not do too much thinking – I like to get home and watch South Park or The Simpsons, and listen to early-2000s indie-rock music – and its probably not the same as their popular culture. And they are all individuals, with different likes and dislikes, so I shouldn’t imagine that their idea of popular culture is particularly uniform, either.

And this presents a serious problem for the historian, albeit one which is a huge amount of fun to try and make sense of. In some ways, the historian’s job is a little easier than someone looking sideways at the world around them today. We now live in a highly commercial age, where every whim and fancy is catered for one way or another. We are encouraged to be ‘individuals’ at every turn: a company selling hair gel does so with the idea that, by buying it, you are somehow sticking it to the man. Identifying a distinctive ‘popular culture’ in today’s world is probably an impossible task. Freud once described ‘the popular’ as being the ‘rebel in all of us’ – but in a world where ‘the rebel’ is a commercial stock-in-trade, even this lovely poetic description soon breaks down. The historian, on the other hand, will usually be accessing a world before rampant commercialisation and before the idea took hold that individuality can be asserted by doing and buying certain stuff – which may make ‘popular culture’ a little easier to identify.

One way of doing so might be to identify what we can think of as ‘elite culture’, take it away, then whatever’s left is the ‘popular’ – the so-called ‘residual’ approach. Most of us probably share with our nineteenth-century forebears an idea about what ‘elite culture’ was (except, of course, for them culture and elite culture were the same thing). I have in mind Burckhardt’s art, music, sculpture and literature of the Italian renaissance; von Ranke’s diplomatic and political systems of 19th-century nation-states; or Gibbon’s pre-Christian Roman Empire as some sort of normative ‘standard’ for culture. Take all that away and examine what’s left: the alehouses, folksongs, dances, ballads, games, stories, food, etc. of the common people. That’ll do, won’t it?

The trouble is that it rather treats the ‘elite’ and the ‘popular’ as two hermetically-sealed opposites, walking in entirely different worlds and speaking different languages. Keith Wrighton and David’s Levine’s famous study of Terling postulated a model of social and cultural polarisation, between the puritan culture of the village elites and the alehouse-sociability of the rest, but drew criticism for its sharp categorisation of the social strata. A good example of why this matters is Samuel Pepys’ trip to the theatre in January 1660/61, where he was greatly troubled by the fact that four junior clerks were sat in better seats than his own 1s 6d box. We’re talking about people who walked in the same streets, and had similar levels of access to different forms of culture. While there might be some ‘gravitational pull’ to one pole or another, there was no clear line in the middle. Pepys himself, of course, enjoyed the alehouse just as much as the theatre! Similar problems exist with just dividing up society according to literacy, with recent studies like Andrew Camber’s Godly Reading convincingly demonstrating that the world of print did nothing to diminish the vitality of oral culture.

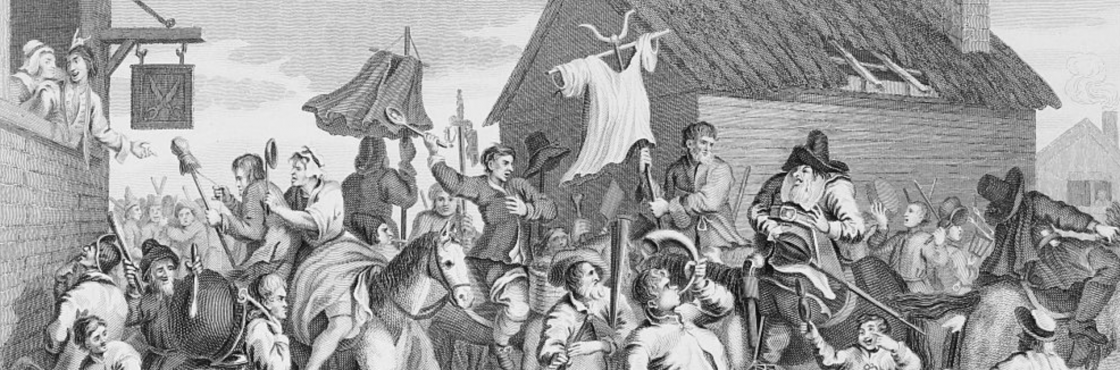

Breugel’s ‘Fight between Carnival and Lent’: the battle-lines seem pretty clear, until you think that, through Breugel, Carnival and Lent are engaging in a dialogue with one another.

The ‘pioneer’ historians of popular culture were never so crude as to assume such clear distinctions. Peter Burke’s seminal Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe distinguished between the ‘Great’ and ‘Little’ traditions – the classical tradition on the one hand, and everything else on the other. But Burke was very careful about pressing this too hard, taking a pan-European approach in the hope of sketching out broad trends and tropes. The ‘settler’ historians have also been careful not to define their subject matter too tightly. This is what Barry Reay said in the introduction to his 1998 Popular Cultures in England, 1550-1750:

The key words for this history are: ambiguous, complex, contradictory, divided, dynamic, fluid, fractured, gendered, hybrid, interacting, multiple, multivalent, overlapping, plural, resistant and shared.

I can’t really argue against this, but my head is spinning: a topic so disjointed is unlikely to provide fertile ground for the historian seeking to make some sense of the past.

At the moment, I’m personally unclear that ‘popular culture’ will ever particularly convincing as a category of analysis. There are just too many grey areas, too much looseness in the definition. The term just encompasses too much all at once – it bites off more than can be chewed, let alone digested. It’s not something that really exists – we usually speak of it to either pejoratively write off something we consider uncultured and crude, or to romantically illustrate some sort of idealised reaction to the stifling, constricting standards of officialdom. That said, a good historical argument is one that is convincing without being just a unfalsifiable truism (thanks, Karl Popper). I’m tempted to say, therefore, that past ‘popular culture/s’ is the perfect material for a university history course, whatever it is.

Interesting thoughts, though I don’t necessarily share your pessimism about ‘popular culture’ as a class of analysis.

What (for instance) about a broadly quantitative definition of popular culture? Something is ‘popular’ if it crops up in a lot of places, or is used by lots of different people? Of course, this raises thorny problems of cultures ‘consumed’ by many people vs. cultures created by many different people, not to mention problems of how historians find evidence for how widespread any given cultural form is. But those problems are technical, rather than analytic…

LikeLike

Good point – you’re definitely right to draw that distinction – and we can certainly endeavour to recover and understand widespread cultural expressions/forms/practices of past societies. ‘Popular’ in the sense of ‘widespread’ doesn’t cause me much concern. Its ‘popular’ in the sense of ‘not elite, of the [common] people’ that I’m wary of, because then you got a very unstable binary division, plus massive methodological problems (mediation probably first and foremost, especially for pre-modern societies) to boot. Thinking about maypoles and morris dancers – certainly widespread, plenty of evidence for that, and have no problem calling it ‘early modern popular culture’ in that broad sense of the word. But ‘elites’ did it too – encouraged it, participated in it, defended it, appropriated it – James I and his son proclaimed in favour of it as a useful weapon to bash other ‘elites’ (sabbatarian puritans) with. Maybe for a later period, when different kinds of source material (esp. into the modern day, when oral testimony can be recovered) its a slightly different story?

LikeLike